Heraclitus was a Greek philosopher who lived before Socrates

in the area of Ephesus (now part of Turkey). Only fragments of a probably

unfinished book he wrote are known to exist. From these fragments, Heraclitus

is believed to have been an independent and self-educated thinker known for

promoting or provoking deeper comprehension of the world. He is probably best

known for his flux principle – no, this has nothing to do with the flux

capacitor popularized in “Back to the Future.” The flux principle as attributed

to Heraclitus in Plato’s Cratylus

involves the notion that all things pass and nothing remains the same, similar

to the flow of a river; one cannot step into the same river twice due to

constant change. Things change. It is the nature of things to change.

Technologies change. Technologies change what people do,

what they can do, what they will do, and what they eventually do. Technologies

change.

People change. People change opinions, beliefs, preferences

and even habits (an interesting and revealing exercise is to extend this list

in a public setting).

Education changes people, or that potential at least exists.

Education involves learning, of course. Learning is fundamentally about change.

Learning has occurred when there is evidence that stable and persisting changes

in what a person or group of people know and can do have occurred. Learning

involves change. Without some evidence of some kind of change one cannot

maintain that learning has occurred. What changes might be involved in

learning? Changes in abilities (e.g., learning to ride a bicycle – try a

unicycle for a challenge), beliefs (e.g., learning about the impact of higher

education on an individual’s earning potential or a country’s economic

productivity), knowledge (e.g., learning how to find the maximum value of a

function), mental models (e.g., internalizing a problem-solving approach for a

class of problems), and so on. Learning is about change. Those who want to

assess learning then need to understand what changes were targeted and the

extent to which changes occurred.

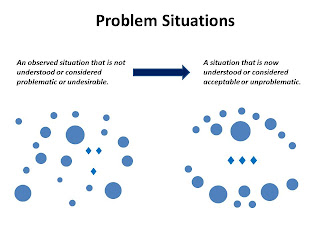

One can argue more generally that problem solving is about

change. Solving a problem in general involves transforming an incomplete or

unacceptable situation into a more complete or acceptable situation. Jonassen

argued that life is fundamentally about solving problems that come in about a

dozen different flavors, with dilemmas being the most challenging. One cannot

avoid problems – like it or not, everyone is compelled to engage in problem

solving – in trying to bring about desired changes, some large and a great many

small, but nearly all unavoidable. Life is about change.

Some things will change regardless of what people do as it

is in their nature, as Heraclitus argued. People can influence some changes.

Those are the focus of projects and programs, which are generally aimed at

transforming a problematic or undesirable or deficient situation into a less

problematic or desirable or acceptable situation. Project and program

evaluation, then, is aimed at determining the extent to which desired changes

occurred and why or why not.

A project or program begins with a problem or problematic

situation, typically identified by a needs assessment. That problem can be

stated in the form of a difference between an actual state of affairs and a

desired state of affairs. For example, the actual retention rate of first year

students at an institution might be 55%. For a variety of reasons, some

financial and some more altruistic, the desired retention rate is set at 75%. A

20% gap exists and that can then become the focus of a project or a program. A

summative evaluation of such a project or program will focus on the extent to

which the 20% gap was reduced. Such an outcomes or impact study is not

difficult to construct and conduct. A likely outcome is that not all of the 20%

gap will be reduced by a particular project or program. The question then

becomes: Why did that happen? To answer that kind of question requires a great

deal of information about and study of how the project or program was designed,

tested, developed, and implemented. Such an investigation is called an

implementation study (in contrast to an impact study) and constitutes a

formative evaluation as the purpose is to improve the project or program as it evolves

so as to improve the likelihood of success in achieving the goals and positive

results in an impact study.

So, an evaluation starts with a problem that identifies a

difference between what is and what is desired. The structure of the project or

program is then based on prior research and theory that suggested things that

are likely to be effective in transforming the problematic state of affairs

into a desired state of affairs. This part of the project or program plan is

called a theory of change. Why would one expect these particular activities or

interventions to be effective in bringing about the desired changes? The

ability to cite prior research and theory lends credibility to a particular

theory of change that is informing or justifying a particular effort.

Theories of change are of course subject to scrutiny, as are

most beliefs and perspectives. Those who fund projects and programs are

typically quite interested in the theory of change that informs why a project

or program is being designed and developed a particular way.

What to make of these random remarks? In the words of Bob

Dylan, “may you have a strong foundation, when the winds of changes shift.”

And, if Heraclitus is right, a theory of change is subject to change as is

everything else. Or, as Bertrand Russell said, you cannot step into the same

river even once. But I just stepped into something and it is causing my head to

spin.